Dr. Fahmy Malak is one of the few people in the state who can get in to see the governor on fifteen minutes' notice. On his way up the steps of the state Capitol, Malak often detours over to a nearby garden and tromps through it to snap off three or four roses. Inside, he lavishes these in his courtly way upon the governor's secretaries, who know him as the benevolent Dr. Malak, a native Egyptian with polished manners and a worldly charm.

In public, Malak likes to do everything with a flourish, and is always chauffeured to court appearances in his state car. To the frequent dismay of prosecutors, not to mention other witnesses waiting to testify, Malak insists that he appear on the stand first. Instead of responding to the lawyers, Malak speaks directly to the jurors when answering questions or explaining his conclusions. Despite his thick accent, his testimony is usually so smooth and convincing that his audience, even the sleepy ones, pay attention. When he has finished, Malak politely thanks the jurors and steps down with confidence. He knows that in Arkansas, his authority is uncontested.

|

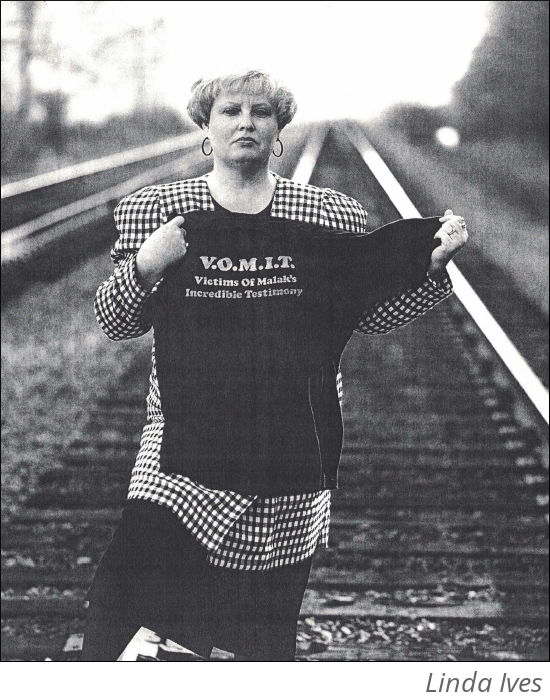

Malak said Linda Ives' son fell asleep on these tracks before he was killed; she has vowed to see Malak thrown out of office—whatever it takes. |

Although he has been supported through two reviews of his job performance, Malak is openly criticized by prosecutors, defense attorneys, and state coroners. Families have been so incensed by Malak's autopsy findings that they have formed a group called Victims of Malak's Infuriating Testimony; (VOMIT) to seek his ouster. Malak has become such an embarrassment that prospective jurors have stated that they are unable to believe his testimony.

And yet he remains in office.

The state's top politicians—including Governor Bill Clinton and State Senator Max Howell of Jacksonville—insist that he is a competent pathologist, despite the controversy that dogs him. The State Crime Laboratory director whose office depends on the veracity and accuracy of Malak's findings, shrugs off questions about the medical examiner, saying he "has no problems" with Malak's performance. Two different state-ordered reviews have found him fit to continue in office.

Last February, Malak's legion of critics had reason to hope that his decade-long reign in the examiner's office as nearing its end, when his autopsy findings on the deaths of two teenagers in Saline County were about to be totally discredited. At the prosecutor's hearing, when his findings were first seriously challenged, Malak rose up uot of the witness box to grant a special dispensation. With is usual flair, he turned to face the parents, witnesses, and prosecutors who had dared question him:

'' I want you to know that I forgive you for everything,'' he said piously, smiling his oily smile.

As the state medical examiner, Malak is the ultimate authority on suspicious deaths in the state, and his rulings are used by police officers, insurance companies, and prosecutors, and accepted as evidence in court. The state medical examiner is supposed to be a medical detective, looking at bodies for evidence of foul play.

Throughout his career, Malak has enjoyed the support of his various bosses—the directors of the state crime lab. Allthough he has threatened the jobs of reporters on occasion, Malak refuses to sit down with them to discuss any of the controversy surrounding his office. Malak's office is virtually unknown to most Arkansans, and is not subject to an judicial review or elective process, but he has become a lasting and dominant figure in the criminal courts of the state.

Part of the problem is the power the state vests in its medical examiner. The medical examiner's responsibilities descended from those of the coroners in the British countryside of the Nineteenth Century, where sheriffs were scarce and a big landowner could award himself an official title and make rulings on questionable deaths himself. In Arkansas, each county has an elected coroner who needs no qualifications beyond being a registered voter with no felony convictions. Historically, many county coroners also have been funeral home owners, as interested in making a sale to the bereaved family as in investigating suspicious deaths.

Coroners are supposed to gather evidence at the death scene and, if foul play is suspected, ask the medical examiner to perform an autopsy. In Arkansas, however, the medical examiner-coroner system lends itself to abuse; the ultimate authority for specifying the manner and cause of death too often rests solely with the examiner—Malak. Short of calling a coroner's inquest, ordering a prosecutor's hearing, or filing suit in circuit court, there is no recourse to challenge Malak's findings.

Dick Pace, president of the Arkansas Coroner's Association, believes that the current system gives too much power to one man. In February of 1988—when Malak had been in office eight years—Pace asked State Attorney General Steve Clark to clarify the duties of the medical examiner. He asked if state law required the medical examiner and the crime lab to work together to determine the manner and cause of death. He wanted to know what was happening with evidence gathered by coroners after it was sent to the medical examiner's office.

Pace never received an answer to his inquiry. Since then, he has helped write legislation that would limit the authority of the examiner's office. The bill, which was tabled in committee in the '89 legislative session, would require other agencies to help establish the cause and manner of death, as well as create a board of appeals for reviewing autopsy findings.

Prior to 1978, the examiner's office was part of the Pathology Department at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. The Legislative Council that year made the office part of the crime lab, which was placed under the new Department of Public Safety. The move was made over the protests of some law enforcement officials who had wanted the crime lab to be either an independent agency or an office of the state police.

Not coincidentally, the strongest criticism of the medical examiner's office has been that it functions as a tool of the state, and that autopsy findings and subsequent testimony are readily slanted to help prosecutors win convictions.

In 1979, State Medical Examiner Dr. Stephen Marx was under investigation by Department of Public Safety Director Tommy Robinson for "burning internal organs after the completion of the autopsy and allowing field agents to rule on the manner of death in numerous cases."

After Marx resigned under pressure, crime lab director Clay White promoted Marx's assistant, Fahmy Malak, in May of 1979. White had hired Malak the previous year as deputy medical examiner. Malak had come to Little Rock from the examiner's office in Chicago, where he was one of many assistants in the examiner's office of Cook County.

Malak is a graduate of Cairo University of Science and Medicine. He came to the U.S. in 1970 for an internship and residency in anatomical and clinical pathology at South Bend, Indiana, and later received forensic pathology training during a fellowship with the Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, coroner at Pittsburgh.

When he was appointed state medical examiner, Malak had not passed his boards in any branch of pathology. In 1979, a new Arkansas statute pertaining to the medical examiner's office specified that the office be held only by a doctor who is either board-certified by the American Board of Pathology (ABP) or at least eligible to take the board examination.

On his third try, Malak became board-certified in forensic pathology in 1985. In February of 1985, the Arkansas Gazette reported that Malak had testified on at least three occasions before 1985 that he was "board-certified." Malak had earned a primary certificate in anatomic pathology from the ABP in I982. (While this certificate recognizes a certain level of competence, doctors who aren't fully board-certified—as Malak was not—generally can't get staff privileges at any major hospitals).

Until ten years after Malak was hired, no review procedure existed for appraising the work of the medical examiner's office. Crime lab directors are appointed by the governor but aren't required to have any training in forensic medicine. Currently, there are no pathologists on either the state crime lab commission or the medical examiner's commission—no one with any qualifications to oversee Malak's work.

Some former employees are so terrified of Malak that they refuse to discuss him under any conditions, hinting that his powers of retribution extend beyond his office. Several of those willing to talk would do so only anonymously.

"Malak plays all these mind games," says a former field investigator in the M.E.'s office, called "Douglas" for the purposes of this article. "He could make it so miserable on you that you'd do what he said. He'd isolate you or ignore you. He has such control. He gets you afraid."

Malak keeps such a tight rein on his staff that his employees are implicitly prohibited from fraternizing with employees of the crime lab, whom Malak considers his personal enemies. (The examiner's office and the crime lab are located in the same building in west Little Rock.)

"[Malak's] reasoning was that he thought these people were possibly out to be against him," states Douglas. "His crew might give out information he didn't want them to have. Malak never told anybody not to associate with anybody else. It was just known."

"You can't even go to the bathroom," a former secretary claims. "When you come back, he'll accuse you of being gone for hours."

In the past twelve years, Malak has had at least ten different assistants. Jesse Chandler, a former field investigator for Malak, had a standing bet with other employees in the crime lab that each new assistant would not last more than six months.

Another former field investigator says he believes that Malak tries to hire assistants and others with questionable credentials and backgrounds. "When something comes up, he can blame it on them. A lot of them realized what Malak was and left in a few months. Malak always gets other people to do his dirty work."

Others say that as long as they were willing to grovel before Malak, they could remain in favor. According to Mike Vowell, a former photographer for the crime lab who once worked closely with the medical examiner's office, Malak feels that "if you're not at his feet, you're at his throat."

Vowell and others point to Malak's sudden, Jekyll-and-Hyde mood swings. Douglas claims that Malak has such a forceful personality that his frightened employees were accustomed to unquestioning obedience.

"Once he feels like you're no longer any use to him, then from then on you're ostracized," notes Chandler. "Malak cared more about power and prestige than money. He never took money from a prosecutor or threw a case for money. He wanted people to praise him and say, 'Oh, Dr. Malak.' He reveled in that so much. He loved people loving him."

Dr. Lee Beamer, now in private practice in Hot Springs, was a friend and colleague of Malak's in Chicago, as well as an assistant in the M.E.'s office here. Beamer claims that Malak is a paranoiac, and Vowell, and others, agree: Malak is a "sick man." Douglas referred to Malak as a "paranoid schizophrenic."

Shortly after Malak was named medical examiner, Beamer and his wife moved to Little Rock, partly at Malak's behest. But Malak soon began to make his old friends uncomfortable.

"He called us every night,'' recalls Nicole Beamer. "He wanted to know what we were doing, what we were eating. He wants to control you completely." Beamer adds that he finally got tired of this and quit taking the calls.

According to Jesse Chandler, who worked in the examiner's office for six years, Malak is in the habit of calling staffers at their homes and treating them as personal servants. He once phoned at 2 a.m. to direct Chandler to come change a tire on his car. Chandler routinely handled personal errands such as picking up Malak's children or buying produce while using a state vehicle. "He'd want to know what was going on. Everybody felt like [the calls] were just another attempt to control everything. Malak didn't know how to sit down on the weekend and be a regular guy."

Aside from attending church, Malak apparently has little social life away from work and still isn't accustomed to American food. At a restaurant in Hot Springs several years ago, Malak and three companions ordered steaks. Instead of using a knife, Malak simply wrestled with the meat until one of his assistant finally leaned over and cut it up for him.

Malak sometimes clipped newspaper ads containing items that he wanted Chandler to purchase.

"Once he gave me an ad with a picture of a saw in it. He said he thought we could use it in the lab to open heads." When he got to Sears, Chandler realized that the ad was for a Black and Decker seven-and-a-quarter inch circular saw. He phoned Malak and talked him out of it.

Chandler feels that, personality aside, some of the problems in Malak's office arise because the chain of command is subverted.

"I thought the director of the crime lab was supposed to be the top boss," Chandler says, "but Malak always got his way. Malak's problem is himself—his desire to control everything. The man didn't trust anybody. He wouldn't tell a cop or anyone about his findings until they told him what they had."

Little Rock lawyer Philip Kaplan has questioned Malak under oath on several occasions and found him to be a difficult and evasive witness.

"At first, I thought it might be attributed to his claim that he was not necessarily familiar with the language," Kaplan explains, "but my view later was that he fully understood....I'm amazed that he remains as the state medical examiner in view of what the directors [of the crime lab] know about him."

Visitors to Malak's office—lawyers, police officers, of family members who come in to see him about autopsy result—must submit to be photographed before he will talk to them. Arguments have ensued with visiting FBI agents over the practice.

"Malak shoots the picture himself with a Polaroid camera," says a former field investigator. "He always makes sure there's a calendar hanging in the background." A lieutenant for a county sheriff''s office in the state confirms that Malak has taken pictures of his staff members on various occasions.

In December of 1988, Malak's former chief field investigator told the Arkansas Democrat that for years Malak had kept various issues of crime lab stationery in his desk. The stationery is updated periodically to reflect the name of a new director. The investigator said that Malak had used the old stationery on occasion to make changes in autopsy reports and had backdated the changes.

Other former employees report that evidence such as bullets and handguns and rifles are mishandled by the examiner's office on a regular basis. Beamer, one of Malak 's former assistants, claims that Malak directed him and other employees to "condemn"—Malak's term for delete information in autopsy reports.

Beamer and the field investigator point out that Malak often takes an unusually large number of photographs during an autopsy. Generally, pathologists will shoot from five to twenty exposures during an autopsy. "I've seen him shoot more than hundred sometimes," Douglas states "He'll only show the ones he wants you to see."

Governor Bill Clinton has also declined to involve himself in the Malak mess, stating that he will abide by the commission's findings.

Dick Pace, president of the Arkansas Coroner's association, says that decisions on the cause and manner of death should be a combined effort of the various agencies involved. Pace also supports legislation that would mandate training for coroners. Currently, only about half of the state's 75 coroners have participated in voluntary training sessions.

Pace believes that the two commissions ,which oversee the state crime lab and the medical examiner's office should be unified and an appeals procedure instituted.

"If family and others didn't agree [with an autopsy finding], they could present it to the prosecuting attorney in their district. He could then go to this board that could overturn it if they thought it was necessary."

Others suggest that the director of the crime lab should be a qualified forensic pathologist rather than a political appointee. "If the director and the commissions don't have the ability to judge Malak, then find somebody who does," says a pathologist who works for the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

The pathologist also suggests that coroners should be replaced by a 'pure' medical examiner system—i.e., free of state control. The system, which now is being used in 21 other states, features a chief medical examiner with satellite offices in different parts of the state, staffed by a medical examiner and utilizing homicide investigators rather than coroners. The investigators report directly to a medical examiner.

"If there's a problem with the [examiner's] office," says Jack Kearney of the Attorney General's office, "it's that it's not independent enough. The state medical examiner should not be the state's tool."

Jim Clark, current director of the state crime lab, agrees:

"If we had a pure M.E. system, to where the medical examiner was separate, [the examiner] could make a better call on the manner of death."

Besides having an examiner too closely allied with the state, the crime lab in Arkansas has never been accredited by the accreditation board of the American Society of Crime Lab Directors (ASCLD). About half the states now have accredited labs, according to Steve Cox, former head of the Trace Analysis division at the state crime lab, but the accreditation process is both expensive and arduous. Along with the latest computer systems and equipment—totally Jacking in Arkansas—each lab must have specified objectives for its director and department heads.

Accredited labs are also subject to periodic review by ASCLD field inspectors, who check to make sure that lab employees receive ongoing training, meet the lab's objectives, and have the basic competence for the job. In addition, the Society requires periodic peer reviews of the medical examiner's work—exactly what has been lacking in the last decade under Malak.

Cox agrees that the lab should be accredited, but adds that, as things stand, "there's no way the crime lab would even get close to being accredited." Like establishing a pure system, accreditation would require funding that doesn't exist. At this point, the only recourse for removing an incompetent or corrupt examiner may be the one that sparked the abortive 1988 reviews of Malak: public outrage.

Dr. Larry Godfrey, an Army pathologist now stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, first met Malak at a medical convention in 1985.

"He needed an assistant," Godfrey explained, "but he was looking for someone who was not board-certified or board eligible in forensic pathology."

In 1988, Godfrey came to Little Rock to apply for a job in the medical examiner's office, as well as to satisfy his own curiosity about Malak. Godfrey had heard from fellow pathologists in the state that, because of questionable practices in the examiner's office, one could literally get away with—or be unjustly convicted of—murder in Arkansas.

Godfrey is certified in forensic, anatomic, and clinical pathologist and was chief of the investigating team after the Challenger shuttle disaster. He is known nationally as a trouble-shooter in his field. Malak, who was under increasing scrutiny at the time, was less than pleased to find Godfrey in his office.

"He seemed to be very paranoid," Godfrey recalls. "He seemed to be concerned that I was there to get a job and force him out of his position."

Most of these anecdotes can be dismissed as personal idiosyncrasies: odd, even bizarre, but not grounds for dismissal. An examination of several recent cases, however, raises questions that go beyond personality quirks: questions about Malak's competence and his integrity.

On August 23, 1987, the bodies of Larry Kevin Ives and his friend, Don George Henry, who both lived near Benton, were discovered on the railroad tracks near Highway 111 west of Alexander. Malak performed autopsies on the boys and, according to their parents, was initially prepared to rule the deaths a double suicide. After consulting with the families, however—who refused to believe the boys had killed themselves—he changed his finding to accidental death.

Malak ruled that the boys, under what he called the "psychedelic influence" of marijuana, had fallen asleep on the tracks and were later run over by the train. Kevin Ives' mother, Linda Ives, and her husband, Larry, along with the parents of Don Henry, sought a second opinion on the autopsy results but were "stonewalled," they say, by the crime lab. Finally they obtained an exhumation order from the circuit court in Saline County.

The results of a second autopsy, by Atlanta pathologist Dr. Joe Burton, conflicted with Malak's finding, and a grand jury was empaneled by Saline County prosecutors Richard Garrett and Dan Harmon. Burton found that both boys had been incapacitated—Don Henry had stab wounds—before they died. Last March, the grand jury found that the boys had probably been killed prior to being hit by the train. A criminal investigation into the deaths was ordered; no arrests have been made to date.

Malak has staked his reputation on that initial autopsy report. On February 21, 1988, he told the grand jury at Benton that, so certain was he that he had missed no evidence, he would quit his job if it was discovered that the boys were killed before the train hit them. Burton's autopsy findings later disputed every aspect of Malak's report. Malak has not offered again to resign.

Steve Cox, former head of the Trace Division at the state crime lab and now an investigator in Atlanta with the U.S. Army, had reason to believe early in the case that the boys were murdered. Cox had examined the boys' clothing and noticed puncture marks. He wanted to match the holes to any marks on the bodies but says he was told by Howard Chandler, the crime lab director at the time, that the case was closed.

"It was obvious to me why I was pulled off the case," Cox says. "It was after I went down to look at the autopsy files on the two boys. I told Malak what I was finding." Cox claims that Malak's autopsy ruling are routinely protected by the crime lab director.

Shortly after Cox was pulled off the case, Howard Chandler received a memo from Malak requesting, in effect, that the Trace Analysis Section keep its opinions to itself. "We were the experts in trace matters," Cox points out, "but he wanted to make the opinion and mold it to his case."

"The facts and the truth were the last things to be looked for in that case, and in general," Cox adds. "There were lots of cases where I felt [Malak] was in error."

Linda Ives founded VOMIT after her difficult in dealing with the crime lab in the death of her son. As the incident and subsequent grand jury testimony unfolded through newspaper accounts, others from across the state contacted Ives about their experiences with the crime lab.

"I've had calls from everywhere," Ives claims. "Some of the things

they've told me Malak has done are incredible."

In a letter to the Arkansas Medical Society dated February 16, 1989, Ives stated five complaints about Malak. The letter was written after consultations with both Malak and Dr. Joe Burton, who performed the second autopsy on her son:

"On September 4, I 987, Dr. Malak tried to force us to look at the autopsy photographs of our son against our wishes.

"On February 9, 1988, Dr. Malak placed specimen jars containing body organs and tissue samples belonging to our son Kevin on his desk in the families' view and commenced a narrative about them.

"Dr. Malak told the Saline County Sheriff's Office and the public that my son would have had to smoke at least 20 marijuana cigarettes to achieve the blood THC content he reported. He had not even quantitated the strength of the marijuana used nor performed any other test to arrive at this conclusion.

"The test performed on my son's blood was designed to be used on urine.

"On February 22, 1988, Dr. Malak insisted on introducing my son's autopsy photographs at the prosecutor's hearings to the public [laypersons] who could not possibly interpret them."

The Medical Society took no action on the complaints, according to Ives.

On more than twenty occasions during his six years with the crime lab, Steve Cox was asked to check Malak's work and concluded that Malak was in error on trace evidence opinions.

"If he saw a smudge pattern on a hand, he called it gunpowder residue," Cox recalls. "He makes an opinion about the cause and manner of death before the facts are in, then fishes for facts to support his pre-formed opinion ... [Malak's staff] knew he was taking their information and making conclusions that weren't appropriate. [Malak] likes to be the Supreme Investigator for the state of Arkansas."

Dan Harmon, the Benton attorney who acted as special prosecutor for a grand jury hearing into the deaths of the two boys in Benton, minces few words in discussing Malak and the examiner's office.

"I think the man's dangerous," Harmon said. "I think he's mentally unbalanced. He's an evil, no-good son of a bitch. He has no honesty, no integrity, and you can quote me on that."

In August 1988, an autopsy ruling by Malak was similarly challenged by the Pulaski County Coroner, Steve Nawojczyk, in the case of an elderly nursing home patient. Malak ruled that the man had died of natural causes, but Nawojczyk believed the man had been beaten to death. In a highly unusual move, he called a coroner's inquest. After only minutes of testimony, the jury agreed unanimously with Nawojczyk.

On the same day, the state crime lab board recommended that Malak's salary be raised by $14,000—from $81,000 to $95,000.

A similar misfire had occurred in 1985, when it was established that he had misused evidence, reached flawed conclusions, and probably lied under oath two years previously in a criminal trial.

The family of David Michel, of Little Rock, was suing Ray Horne for $3.8 million in damages. Horne's son, William, had been convicted of first-degree murder in 1983 in the beating death of Michel in a west Little Rock parking lot.

During the original murder trial, Malak had shown a photographic transparency of the butt of a 30-30 rifle—the alleged murder weapon—which he said would match a bruise on the life-sized photo of Michel's collar bone. A nick in the butt of the gun, Malak said, matched a tiny irregularity in the bruise when he placed the transparency over the photo.

In the civil trial, in June 1985, Malak had cited the same evidence in his testimony. This time, however, Ray Horne's attorney, John Lisle of Little Rock, discovered that the transparency of the rifle butt was being used incorrectly.

Lisle, a former bayonet instructor, said that when Malak placed the transparency over a life-sized photo of the bruises on Michel's collar bone, he could read the name of the gun, "Marlin." Lisle pointed out that the name should have read in reverse on the transparency; the reproduction had been flopped. After Lisle pointed this out, Malak flipped the transparency over but was then unable to make the rifle butt match the bruise.

Before placing the transparency over the photo, Malak had testified that the transparency of the rifle butt and the photo of Michel's body corresponded "one-to-one," and that the rifle butt would match the bruise like "a rubber stamp."

After Lisle discovered the error with the transparency, Malak offered to demonstrate with the rifle how the bruise could have been inflicted. He was still unsuccessful.

In the spring of 1983, William Horne had been convicted of shooting and wounding a friend of Michel's in the same incident, but no eye-witnesses testified to having seen Michel's beating. Horne contended that Michel had tried to jump from the top of an tractor-trailer into the bed of Horne's pick-up truck.

Police officers had spent nine months trying to link Horne to Michel's death. Malak's use of the transparency in court finally made that connection—and insured Horne's conviction.

When it was introduced as evidence in Horne's second trial in 1983, defense attorney Wayne Lee told the judge that he had not seen the transparency during the pre-trial discovery process. After Malak then told the judge he'd had the transparency in his possession for several months, it was admitted as evidence. An Arkansas Gazette reporter, Bob Wells, found out in 1988 that crime lab records showed that the transparency or the rifle butt was made only a few days before the trial.

Malak also testified that he had done the autopsy on Michel, but former crime lab photographer Mike Vowell states that Malak was not present the night the autopsy was performed. The autopsy was performed by Malak's assistant at the time, Dr. Raj Nanduri, who ruled "death at the hands of another.'' The next day, a second death certificate inexplicably ruled the cause as "undetermined." Nine months later, Malak again changed the autopsy ruling to homicide, and Horne was charged with murder.

Vowell, who was present at the autopsy, says he took a picture of the bruise on Michel's collar bone but that it was considered insignificant at the time.

Vowell recalls that he first refused to make the transparency but that Malak insisted. When Vowell asked Malak if he planned to use it in court, Malak told him it was for his own use. Vowell then made the transparency but placed it in a border so that it could not be reversed accidentally when placed over the photo of the bruise. He also glued on a disclaimer stating that the transparency of the rifle butt and the photo of the bruises were not a "one-to-one" correspondence.

When the transparency was produced in court during Horne's criminal trial, however, both the border and the disclaimer were missing.

Recently, a newspaper reporter tried to locate the photo that Malak had used in his testimony. It is missing from the case file of prosecutor Chris Piazza.

Horne's conviction later was overturned, but he eventually pied guilty to a reduced charge of second degree murder. He was sentenced to twenty years. Buster Schmidt, Horne's brother-in-law, contends he has been denied parole for maintaining his innocence.

After the Arkansas Democrat published Vowell's charges, he was fired by Bill Cauthron, then director of the crime lab, for "insubordination, obstruction of internal operation, and violating the Arkansas code that sets guidelines about how crime lab information is released."

The only way to resurrect the crime lab so it can be credible is for Dr. Malak to be fired or to be gone," contends Dan Harmon, who first successfully challenged Malak's findings. "But they've expended so much energy in defending him, how are they going to get rid of him?"

Malak has been supported through considerable controversy in recent years by the Clinton administration, the attorney general's office, several crime lab directors, and the medical examiner's board. Dan Harmon, Linda Ives, and others who have encountered Malak in various capacities would like to know why.

According to John Lisle, the state could be held liable under the 1983 Civil Rights Act for establishing a discriminatory policy or pattern of abuse through the crime lab. To discredit Malak could leave the state open to a flood of litigation from convicts imprisoned on the strength of his testimony.

"Let's assume he perjured himself on a regular basis and the state was aware of this and should have done something about it. Instead, they come back and ratify everything he's done. By doing that, [the state] may have established that pattern."

Lisle feels, however, that soon there may be a resolution of the controversy around Malak's office. "The people on the commissions, the governor and others, in their heart of hearts, would like to see this problem go away. There may be some subtle pressure on him to move on."

Gov. Bill Clinton—whose mother, Virginia Dwire Kelly, is a nurse anesthetist who, according to information uncovered by Mel Hanks of KARK-TV, has worked on at least one case that came under Malak's examination—took until 1988 to ask the crime lab to review Malak's performance. In March 1988 the board hired Dr. David Wiecking, medical examiner in Richmond, Virginia, and Dr, Russell Zumwalt, assistant medical examiner in Albuquerque, New Mexico to review Malak's job performance. Wiecking was later subpoenaed by Dan"Harmon in the Saline County case, and was replaced by Dr. Garry Peterson, medical examiner of Hennepin County, Minnesota.

Employees who worked for Malak at the time say the doctors only spent about thirty minutes in the examiner's office and never asked them about procedures there. In their report, the doctors neglected to comment on any of Malak's cases. They concluded that Malak was overworked and had been victimized by "an unenlightened press." They did note, however, that Arkansas law put Malak "in the weak position of being a consultant rather than an independent official protecting the interest of the citizens."

Four days before the doctors released their findings, the medical examiner's commission met for the first time in more than ten years, to review Malak's performance in the face of mounting public criticism. The commission decided that it didn't have sufficient evidence to relieve Malak of his duties.

Board chairman Dr. Jocelyn Elders, director of the State Health Department, later told the press that the examiner's commission "doesn't have the skills" to judge Malak. Former crime lab director Bill Cauthron also admitted that he "didn't have the expertise" to assess Malak's work.

Another of Malak's supporters has been State Senator Max Howell, the veteran lawmaker from Jacksonville who also has a law firm in Little Rock.

"If Max Howell wanted testimony in any kind of case," Harmon claims, ''Malak would say anything he was asked to say or told to say."

Beamer recalls that shortly after he started work in the examiner's office, a man identifying himself as Max Howell called asking for autopsy results. Malak was out of the office and Beamer initially refused to give out the information.

"Boy," exclaimed the caller, "don't you know who I am?"

Beamer released the information. Howell declines to respond to those charges, saying, "I don't want to get concerned in someone's local politics."

In May of 1988, Howell was named chairman of a select committee of legislators formed to review the authority and responsibility of the medical examiner's office. At the time, Malak had been criticized heavily in the media for his autopsy findings in the deaths of the two boys at Benton.

Prior to the legislative committee hearing, Little Rock newspapers quoted Howell as saying that his "concern was that [Malak] not be indicted for those deaths. I have an admiration for the way Dr. Malak has handled his office."

Linda Ives was upset after reading Howell's comment, and phoned him.

"I told him that he ought to at least try to be objective about the hearing and, if he couldn't, he should resign. The first thing he said to me was, 'Do you known who you're talking to?' Then, he laughed at me. It ended up an absolute screaming match. I was stunned by his whole attitude."

On the first day of the hearing, crime lab director Jim Clark and others led off with tributes to Malak's dedication to his job and competence as medical examiner. Finally, Buster Schmidt, William Horne's brother-in-law, asked if he could speak and Howell waved him to the microphone. "Right after I began to read," Schmidt recalls, "Howell became visibly upset. He tried to hush me up but I went ahead and read the statement. When I finished, the room broke into applause."

Although others followed Schmidt with complaints about Malak, the hearing concluded after one day of testimony, and the committee lauded Malak's job performance to the media. "The hearing," Howell contends, "settled the matter as far as I was concerned.'' He says he heard no criticism of Malak that was relevant to the issue.

At the time, Harmon was still conducting the grand jury hearing into the deaths of the two boys in Saline County. "I had sent word to Max Howell that I was going to send him a subpoena to appear a our grand jury. If he wanted to hear about Malak, we'd just let him participate in our grand jury hearing, and we'd subpoena all the records where Malak had testified in [Howell's] civil cases. I never heard another word from him."

Harmon claims that Malak has worked as an expert witness in civil cases for Howell's law firm. "Malak," Howell responds, "has never worked on any case for my firm that I'm aware of."

The most plausible explanation for Malak's clinging to his post may be the simplest: that Malak's unfitness for office, his unscrupulous approach to evidence, and his penchant for vendettas are well known; but that no one in state government has the courage, will, and patience to prove it and finally have him removed.

For the moment, Dr. Malak remains in his office, secluded from the press, only venturing out when required to testify in court. Perhaps he is wondering who might be out to get him, or when his past might catch up with him. Perhaps his legendary self-esteem has survived his latest ordeals intact.

As long as state officials continue to allow him to play the role of Supreme Investigator for the state of Arkansas, Malak remains secure in his domain, accountable to no one. But outside, the cries of indignation grow louder and more insistent.